3AM.Magazine, 2025

translated by Tobias Ryan, in 3AM.Magazine, initially published in French, in Zone Critique and as a postface to Suzanne (Editions Le Chemin de Fer).

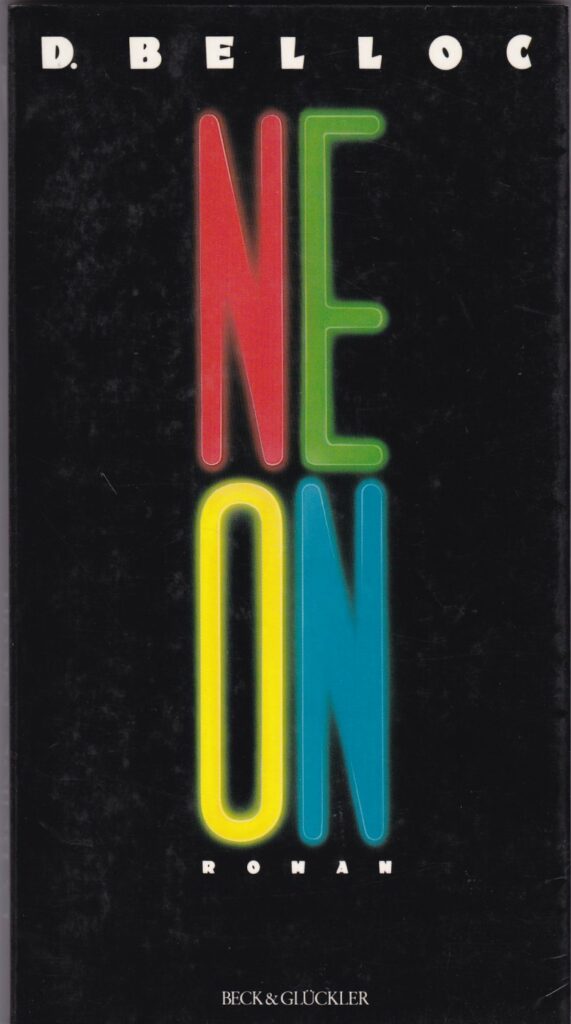

« I had caught a glimpse him among the noisy characters of a bygone age, retrospectively, as their names were nothing more than echoes. On the shelf, his books rubbed shoulders with Hocquenghem, Dustan, Guibert, Collard, and several other. I had found them second-hand, and by a luck worthy of notice, found out that his first novel, Néons, was to be republished, seeming to loom from the inexhaustible reserves of the forgotten.

This inaugural blow had initially, however, been recognized by an strange fairy godmother. Marguerite Duras herself had singled him out with an accusing finger. A gesture (and a long interview in Libération) with which she had embraced the text, stripping it to the bone, and knighting its author. But fairies are as powerless as the Lord above when it comes to guaranteeing one’s destiny.

Belloc was certainly not the author of just one book. Others had followed, up until 2000: Suzanne on his mother’s youth and his father who died from a heavy blow taken in a boxing match; Kepas about dope; and several novels torn from what Duras called “the social night”. And then nothing. We went from the years of AIDS to those of the PACS. The rest died, and he, the only prole, was silent, exhausted by alcohol and smack, so one of his American fans reported. And perhaps that’s how he would have summed it up: pisses me off. The cry of a man who could no longer avoid the obvious: in the literary milieu he was never on anything but borrowed time.

It’s beautiful but it’s seedy, says the tranny Triche in Les Ailes de Julien. She is lecturing a young runaway who is discovering nighttime Paris. “On the days when it’s dark, I forbid you from loving the night!” she says. Aren’t the places that go beyond seedy those to which we must descend in order to write? It is with a wary eye one must approach Belloc’s books. He wrote too little and too much. Two ley lines are traced across frequently autobiographical terrain: that of the family, a violent father, drunken mother, and fugitive son, and, within this triangle, a swamp: the threat of incest or insult, welts and shiners, brazen language as tight as a net from which it seems you will never escape; and secondly, the world of queens, fixes, and prostitutes, soft cries which break through the night heading back up Boulevard de Clichy, not whore folklore but a solitude so defiled that you no longer exist. A kind of coma, Belloc sighs, where nonetheless a desire for purity exists. But one which leads to suicide. You have shown us the night in your head, Duras said… »